Paper – Discussion Paper on Proposed Federal Accessibility Legislation and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2017)

This paper addresses an important legal issue ARCH recommended the Government to address as it developed the proposed federal accessibility legislation: the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and its relationship with the planned federal accessibility legislation.

In this paper ARCH provides a legal analysis of the role that the Convention has played in Canadian jurisprudence until 2016 and makes recommendations for strengthening the relationship between the Convention and the proposed federal accessibility legislation.

ARCH’s Discussion Paper on Proposed Federal Accessibility Legislation and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was presented to government in its consultation process as it developed the new accessibility legislation in 2016.

This resource is part of ARCH’s Advocating for an Accessible Canada initiative. For more information about the initiative, go to: www.archdisabilitylaw.ca/initiatives/advocating-for-accessibility-in-canada

This resource is also part of ARCH’s Advancing UN CRPD initiative. For more information about the initiative, go to: www.archdisabilitylaw.ca/initiatives/advancing-the-un-crpd

PDF and RTF versions of this submission are available at the end of this page.

Introduction

In 2016, the Government of Canada announced its intention to develop and introduce federal accessibility legislation. The goal of the proposed legislation is to promote equality of opportunity and increase the inclusion and participation of Canadians with disabilities.[1]

The Government of Canada has stated that new federal accessibility legislation would apply to organizations and areas that fall under Federal legislative jurisdiction.[2] Federal jurisdiction includes, for example, banking, inter-provincial transportation, telecommunications, federally-regulated employment, federally-regulated services such as Canada Post and Government of Canada services, criminal law, and some indigenous issues.[3]

ARCH Disability Law Centre is engaged in the Government’s process of consulting with Canadians as part of its development of the new accessibility legislation.[4] ARCH has identified several important legal issues, which we recommend the Government address as it develops the proposed federal accessibility legislation. This paper discusses one of these issues: the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities[5] (Convention)and its relationship with planned federal accessibility legislation. In this paper we provide a legal analysis of the role that the Convention has played in Canadian jurisprudence to date. We make recommendations for strengthening the relationship between the Convention and the proposed federal accessibility legislation.

About ARCH

ARCH Disability Law Centre (“ARCH”) is a specialty legal clinic dedicated to defending and advancing the equality rights of persons with disabilities in Ontario. ARCH is primarily funded by Legal Aid Ontario. For over 35 years, ARCH has provided legal services to help Ontarians with disabilities live with dignity and participate fully in our communities. ARCH provides summary legal advice and referrals to Ontarians with disabilities; represents persons with disabilities and disability organizations in test case litigation; conducts law reform and policy work; provides public legal education to disability communities and continuing legal education to the legal community; and supports community development initiatives. More information about our work is available on our website: www.archdisabilitylaw.ca

ARCH has a longstanding history of representing parties and interveners before courts and tribunals in matters that raise systemic human rights and accessibility issues within both the federal and provincial jurisdictional spheres. ARCH lawyers have appeared before the Canadian Human Rights Commission, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, and all levels of court including the Supreme Court of Canada. ARCH has made extensive submission to reforms of Ontario’s Human Rights Code and the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act. ARCH is currently a partner in drafting a shadow report to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on Canada’s implementation of the Convention.

Why is the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Relevant to a Discussion about Federal Accessibility Legislation?

The Convention is an international treaty which sets out a legal framework to promote respect for the dignity of persons with disabilities and promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and freedoms by persons with disabilities.[6] The Convention builds on a significant body of international treaties, conferences and programs that have recognized rights for persons with disabilities.[7]

The Convention is important and highly relevant to the discussion, development and drafting of the federal accessibility legislation for the following reasons:

Ensuring that Canada’s federal accessibility legislation is in keeping with the most up-to-date, global framework for disability rights: The text of the Convention is the result of significant negotiation between states and significant participation of civil society groups representing persons with disabilities from around the world. The involvement of so many persons with disabilities and their representative groups in the development and negotiation of the Convention lends it authenticity and credibility as a significant global commitment to a human rights framework for people with disabilities.[8] Given the significance of the Convention, it is an important source and starting point when new disability-related legislation, like the federal accessibility act, is created.

Ensuring that Canada complies with its international legal obligations under the Convention: Canada signed the Convention in March 2007 and ratified it in March 2010.[9] By signing and ratifying the Convention, Canada bound itself to the treaty and assumed responsibility for ensuring respect for its obligations thereunder.[10]Ratification was, therefore, a significant step in confirming Canada’s commitment to the principles and obligations set out in the Convention. In order for the Government of Canada to ensure that it is meeting these international obligations, consideration must be given to the Convention when developing and drafting the federal accessibility legislation.

Ensuring that the Government of Canada achieves its stated intention of creating federal accessibility legislation that addresses accessibility proactively and systemically: The Government’s stated intention is to create federal accessibility legislation that will take a proactive, systemic approach to accessibility, in order to advance the inclusion and equality of persons with disabilities in Canada.[11] In a similar vein, the Convention includes a number of obligations which are intended to address accessibility issues in a proactive and systemic way. Many of the Convention obligations are relevant for Canada’s federal accessibility legislation.

The Convention’s Limited Impact on Canadian Jurisprudence

The Government of Canada’s ratification of the Convention was an important commitment to advancing the status of persons with disabilities in Canada. Having ratified the Convention, many persons with disabilities, and indeed many disability rights activists, think of the Convention as the law of the land in Canada. However, due to Canadian federalism and jurisprudence, this is not the case.

Generally in Canada, international treaties liked the Convention are only enforceable if they have been expressly incorporated into Canadian domestic law. Express incorporation is most often accomplished by the introduction of new legislation that specifically adopts the international treaty into Canadian law, or by the passing of Canadian domestic law that adopts the language of all or parts of the international treaty.[12] Thus, international treaties are not automatically incorporated into Canadian domestic law when Canada ratifies the treaty.[13]

Although Canada has ratified the Convention, the Government of Canada has not enacted legislation to incorporate the Convention into Canadian domestic law. This presents legal and practical barriers to implementing and enforcing Convention rights in Canada.

Because Canada has ratified but not incorporated the Convention into domestic law, Canadian courts and tribunals generally do not view the Convention as binding law in Canada. Rather, Canadian courts and tribunals typically view the Convention, like other unincorporated international treaties, as a source of law which can be used to inform the interpretation of Canadian domestic law.[14] Where possible, Canadian courts will interpret and apply domestic law in a manner consistent with the Convention.[15] Canadian courts and tribunals generally do not rely on the Convention as authority for novel legal decisions, and persons with disabilities or groups representing them cannot bring a legal action for breach of the Convention before a Canadian court or tribunal.

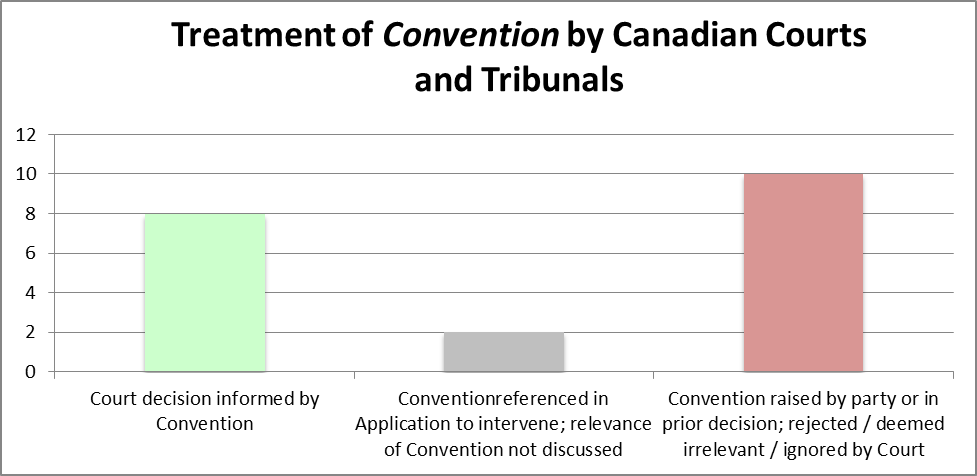

ARCH undertook a review and analysis of reported court and tribunal decisions in which the Convention is raised.[16] Our review demonstrates that to date, the Convention has had a limited impact on Canadian jurisprudence. To date, only 20 reported court and tribunal cases in Canada have addressed the Convention.[17] This is a surprisingly small number, given that Canada ratified the Convention close to seven years ago, and given that a disproportionately large number of cases before provincial/territorial and federal human rights tribunals raise complaints of discrimination on the basis of disability.[18] The chart below shows that of these 20 cases, 8 treated the Convention positively (meaning the court or tribunal’s decision was informed by the Convention), 10 treated the Convention negatively (meaning the court or tribunal rejected using the Convention as a basis for its reasons in the case), and in 2 cases the Convention was raised by the litigants but was not particularly germane to the issues before the court.

Figure 1: Treatment of Convention by Canadian Courts and Tribunals

In all of the 8 cases that treat the Convention positively, the Convention is used as an interpretive aid, to assist the court or tribunal to understand the meaning intended by the particular Canadian law that is at issue. For example, Hinze v. Great Blue Heron Casino[19] was an application alleging discrimination on the grounds of disability. In determining that the applicant was not disabled within the meaning of Ontario’s Human Rights Code, the Tribunal explained that it would be using a social model definition of disability. The Tribunal relied on the Convention and various Supreme Court of Canada decisions to support its use of a social model definition. Further, in Geldart v. Geldart[20] the Court considered a motion to dismiss a default judgment that was based on the moving party’s failure to attend a scheduled hearing. The Court set aside the default judgment, applying the applicable Rules of Civil Procedure in a manner allowable by their plain wording, but also consistent with existing Canadian jurisprudence and Article 13 of the Convention. In keeping with the Supreme Court of Canada’s decisions in Hape[21] and Baker,[22] the Convention plays a supporting role in these decisions. It is used to support a legal finding or outcome that can already be found in existing Canadian law. It is never used as the primary reasoning in a case.

With respect to the 10 cases that treat the Convention negatively, there are various approaches taken by courts and tribunals. In some decisions, appellate courts overturn trial court decisions in which judges have reasoned in favour of Convention rights and obligations. In some decisions courts and tribunals reject any reliance on the Convention based on its status as a ratified but unincorporated treaty. And in several cases litigants raise arguments based on Convention rights and obligations but these arguments are found to be irrelevant or are ignored by the court.

The cases also demonstrate that judges will not overrule domestic legislation that explicitly conflicts with the Convention. For example, in the 2011 case Cole v. Cole[23], a father and mother were divorced and each was applying to be the substitute decision maker of their adult son who had disabilities. The father also argued that he still had custody of the son. The adult son with disabilities argued that his father did not have custody because once he became an adult he had legal capacity, was legally entitled to make his own decisions, and should be provided with supports to do so, in accordance with Article 12 of the Convention.[24] The Court disagreed with the son. The Court found that the father still had custody because Canada’s Divorce Act considers a person over the age of 18 to be a “child of the marriage” if they are unable because of their disability to live independently.[25] The judge stated that he found the arguments about legal capacity and the Convention to be “interesting and worthy of consideration”, but nevertheless he could not derogate from the finding that the custody order still applied to the adult son on the basis of his disability because that is what Canadian law provides for.[26] This case illustrates that although Canada has ratified the Convention, Canadian courts will not enforce Convention rights if they conflict with Canadian domestic law.

Even where there is no conflict between the Convention and domestic law, the fact that Canada has not incorporated the Convention into Canadian domestic law prevents some decision makers from applying the Convention or enforcing the obligations contained therein. For example, in BS (Re)[27] the applicant’s health practitioner brought an application before Ontario’s Consent and Capacity Board to determine whether BS’ spouse had complied with the requirements of the Health Care Consent Act when deciding about a proposed palliative care treatment plan for BS. BS argued that under Article 25 of the Convention persons with disabilities have the right to enjoy the highest attainable standard of health without discrimination. The Board found that the Convention did not apply to the case. The Board stated that, “it is unclear what applicability the Convention has here absent ‘transformation’ into Canadian law and no evidence was led related to discrimination.”[28]

In Nova Scotia (Community Services) v. C.K.Z.,[29] the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal overturned a Family Court decision that relied, in part, upon the Convention to dismiss an application by the Minister for permanent care of two children born to a couple with intellectual disabilities. The Family Court analyzed the best interests of the children, and as part of this analysis considered whether appropriate disability services and supports had been provided to the parents. The Family Court relied upon Article 23 of the Convention, which provides for respect for the home and family. The Court of Appeal ruled that the trial judge did not focus appropriately on the best interests of the children and erroneously focused on the parents. The Court of Appeal found that the trial judge did not follow domestic legal precedent and instead erroneously relied on the Convention to support a new kind of best interests of the child analysis. The Court of Appeal also commented that it is unclear how two ratified international treaties, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, should interact in this instance absent domestic incorporation.[30] This case is, arguably, not one in which the Convention clearly conflicts with Canadian domestic law, but rather a case in which it is possible to interpret Canadian domestic law in various ways, one of which gives life to Article 23 of the Convention. The Court of Appeal decided that the correct interpretation was one which strictly followed existing Canadian jurisprudence, demonstrating that absent incorporation into domestic law, courts may be reluctant to interpret Canadian law in a manner that gives life to the Convention, even where the Convention is clearly relevant to the issues raised in the case.

The above analysis of reported court and tribunal decisions in which the Convention is raised demonstrates that as a ratified but unincorporated international treaty, the Convention has thus far had a limited, contextual role in Canadian law. It has been mentioned in only a small number of decisions since ratification, and a smaller number still have treated the Convention positively. These positive treatments all use the Convention as an interpretive aid to support a decision that is also supported by existing domestic law. Most, if not all of these cases would have been decided the same way, regardless of whether the Convention was relied upon. Decisions that treat the Convention in a negative light have done so for a variety of reasons, including lack of incorporation into domestic law, conflict with domestic law or jurisprudence, and deemed irrelevance. On multiple occasions the Convention has been raised by a party, but not addressed by a court or tribunal. The cases demonstrate that the lack of incorporation into domestic law presents a legal barrier to greater enforcement and compliance with the Convention in Canada.

The Convention Provides a Framework for the Federal Accessibility Legislation

It is our view that the creation of federal accessibility legislation provides an excellent opportunity to promote and advance disability rights in Canada by enhancing Canada’s compliance with its obligations under the Convention. Many of the Convention obligations are relevant for Canada’s federal accessibility legislation. ARCH recommends that the Government of Canada adopt and incorporate specific obligations, language and concepts from the Convention into the new federal accessibility legislation. Doing so would achieve a number of objectives, including:

- Helping to ensure that the Government achieves its stated intention of creating legislation that addresses accessibility proactively and systemically;

- Helping to ensure that Canada complies with its international legal obligations under the Convention;

- Helping to remove the legal barrier that prevents Canadian federal courts and tribunals from adjudicating Convention rights;

- Helping to ensure that Canada’s federal accessibility legislation is in keeping with the most up-to-date, global views on disability rights;

- Sending a message to Canada’s disability community and the international community that Canada is a leader in disability rights, inclusion and accessibility.

The Convention contains a number of obligations that would be appropriate to incorporate into the federal accessibility legislation. Some Convention articles can be substantially adopted as is into the federal accessibility legislation, while others will require modification and adaptation. Where possible, the language of the Convention should be mirrored in the federal accessibility legislation.

ARCH recommends that the following articles be adopted and included in the federal accessibility legislation[31]:

Article 3, which sets out the General Principles that are applicable to all the articles in the Convention. The federal accessibility legislation should include a provision setting out its own general principles which, like those listed in the Convention, would be useful to assist in interpreting and applying the specific obligations established by the federal legislation. Of the General Principles included in the Convention, the federal legislation should include, at minimum, respect for inherent dignity and independence of persons, full and effective participation and inclusion in society, equality of opportunity, and accessibility.

The federal accessibility legislation should, in its Preamble, refer to the Convention as the source of some of the requirements established by the new legislation.

Article 4, which establishes General Obligations on states. Subsections 1 (f), (g), (h), and (i) are particularly relevant for the federal accessibility legislation. Subsection 1(f) requires states to “undertake or promote research and development of universally designed goods, services, equipment and facilities, as defined in article 2” of the Convention, requiring the minimum possible adaptation and the least cost to meet specific disability-related needs, to promote their availability and use, and to promote universal design in the development of standards and guidelines. Subsection 1(g) requires states to “undertake or promote research and development of, and to promote the availability and use of new technologies, including information and communications technologies, mobility aids, devices and assistive technologies, suitable for persons with disabilities, giving priority to technologies at an affordable cost”. Subsection 1(h) requires states to “provide accessible information to persons with disabilities about mobility aids, devices and assistive technologies, including new technologies, as well as other forms of assistance, support services and facilities”. Subsection 1(i) requires states to “promote the training of professionals and staff working with persons with disabilities in the rights recognized in this Convention so as to better provide the assistance and services guaranteed by those rights”. Each of these subsections of Article 4 should be adopted and incorporated into federal accessibility legislation.

Article 6, which requires states to take steps to address the unique discrimination faced by women and girls with disabilities. In the same vein, the federal accessibility legislation should recognize the unique barriers to accessibility faced by women and girls with disabilities, and should ensure that any accessibility requirements pay special attention to removing these barriers.

Article 9, which addresses accessibility. Most, if not all, of the requirements set out in Article 9 should be adopted into the federal accessibility legislation.

Article 13, whichaddresses access to justice and requires states to ensure that persons with disabilities have equal and effective access to justice. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that federal courts, tribunals and other administrative decision-making mechanisms are fully accessible to persons with disabilities. This would include requirements for federal courts and tribunals to provide procedural and age-appropriate accommodations during all stages of legal proceedings including investigative and other preliminary stages. The federal accessibility legislation should create accessibility training requirements for federal court and tribunal staff, adjudicators, and judges.

Article 20, which addresses personal mobility for persons with disabilities. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that federally regulated transportation is fully accessible for persons with disabilities. This should include requirements for transportation services staff to be trained in accessibility. It should also include facilitating transportation in the manner and time of choice of the person with a disability, and at affordable cost.

Article 21, which addresses freedom of expression and access to information. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that the Federal Government and federally-regulated service providers, employers and other entities provide information in accessible formats and technologies appropriate to different kinds of disabilities in a timely manner and without additional cost. The federal accessibility legislation should require the Federal Government and federally-regulated service providers, employers and other entities to accept and facilitate the use of sign languages, Braille, augmentative and alternative communication and other accessible forms of communication. The federal accessibility legislation should require internet-based services and information to be provided in accessible formats for persons with disabilities.

Article 27, which recognizes the right of persons with disabilities to work on an equal basis as others. The federal accessibility legislation should obligate the Government of Canada and other federally-regulated employers to ensure that all aspects of employment are accessible, including recruitment, hiring, employment conditions, career advancement and retention. Careful attention must be paid to ensure that the federal accessibility legislation works in tandem with existing federal legislation, such as the Canadian Human Rights Act, Employment Equity Act, and other relevant laws. Substantial consultation with the Canadian Human Rights Commission is required. Article 27 also provides for effective access to technical and vocational training, placement services, and the promotion of self-employment and entrepreneurship, all of which should be considered for inclusion in the federal accessibility legislation.

Article 28, which addresses adequate social protection for persons with disabilities. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that Canada’s existing income support and social security programs are fully accessible to persons with disabilities, including application and appeal procedures. The federal accessibility legislation should require the Government of Canada to develop a national action plan that addresses poverty reduction for persons with disabilities. This plan should address access to adequate food, clothing and clean water; access to appropriate and affordable disability services, assistive devices and other disability-related needs; and access to affordable, accessible housing. This plan must include goals, concrete ways of measuring goal attainment, and timelines for doing so.

Article 29, which addresses participation in public and political life. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that federal voting procedures, facilities and materials are fully accessible to all persons with disabilities. Attention must be paid to accommodate persons with various disabilities, including providing plain language voting information for persons labelled with intellectual disabilities and ensuring that voting procedures can accommodate augmentative and alternative communication. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that all-candidates meetings and other election-related events are fully accessible for persons with disabilities. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that persons with disabilities have equal access to running as political candidates, including access to funding to off-set the costs of disability-related campaign and accommodation expenses.

Article 30, which addresses participating in cultural life, recreation, leisure and sport. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that persons with disabilities enjoy access to federally-regulated television, radio and telecommunications. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that all federally-regulated museums, galleries, libraries, national parks and other cultural sites and services are fully accessible to persons with disabilities. This includes provisions to ensure that laws protecting intellectual property rights do not constitute an unreasonable barrier to access by persons with disabilities to cultural materials. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that national sport programs are fully accessible to persons with disabilities.

Article 31, which addresses statistics and data collection. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that any public statistics and data which the Government of Canada collects are fully accessible to persons with disabilities. The federal accessibility legislation should provide that statistics and data will be collected and used to help assess the implementation of the obligations under the legislation, and to identify and address barriers faced by persons with disabilities.

Article 32, which addresses international cooperation. The federal accessibility legislation should ensure that Canada’s international cooperation, including international development programmes, is inclusive of and accessible to persons with disabilities.

In addition to the Articles above, the Convention addresses a number of important issues that fall within provincial/ territorial jurisdiction in Canada, include Article 12, which addresses legal capacity and supported decision-making, and Article 24, which addresses inclusive education. The federal accessibility legislation should address the need for the Government of Canada to develop national strategies on these issues.

Conclusion

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities establishes a significant legal framework to protect and promote the human rights of persons with disabilities. Although Canada ratified the Convention nearly seven years ago, our analysis demonstrates that the Convention has had a limited impact on Canadian jurisprudence to date.

ARCH recommends that the Government of Canada adopt and include select, specific obligations, language and concepts from the Convention into the new federal accessibility legislation. Doing so would help to ensure that Canada complies with its international legal obligations under the Convention;help to remove the legal barrier that prevents Canadian federal courts and tribunals from adjudicating Convention rights;help to ensure that Canada’s federal accessibility legislation is in keeping with the most up-to-date, global views on disability rights;and send a message to Canada’s disability community and the international community that Canada is a leader in disability rights, inclusion and accessibility.

Importantly, including Convention obligations and language in the federal accessibility legislation will help to ensure that the Government of Canada achieves its stated goal of creating legislation that addresses accessibility proactively and systemically. The Convention already provides a blueprint for achieving accessibility. It is an important source to be considered when developing and drafting the proposed federal accessibility legislation.

Moreover, the Convention addresses the human rights of persons with disabilities

more broadly, beyond issues of accessibility. It addresses, for example,

employment, education, legal capacity, awareness-raising, living independently

in the community, liberty and security of the person, respect for home and

family, and many other important disability rights. The current consultation

process is an opportunity to consider whether a broader approach, beyond

accessibility, is needed in order to protect, promote and advance the status of

persons with disabilities in Canada.

References:

[1] Employment and Social Development Canada, Accessibility Legislation: What does an Accessible Canada mean to you? Discussion Guide (Government of Canada, 2016), online: <https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/esdc-edsc/documents/programs/disability/consultations/No.653-Layout%20Discussion%20Guide-EN.PDF>

[2] Ibid at 4.

[3] Ibid.

[4] The Government of Canada’s consultation process involves public consultation events and online feedback. See Employment and Social Development Canada, Consulting with Canadians on accessibility Legislation (Government of Canada, 27 October 2016), online: <https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/disability/consultations/accessibility-legislation.html>

[5] United Nations, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 13 December 2006, A/RES/61/106 (entered into force 3 May 2008) [Convention.]

[6] Ibid at art. 1.

[7] Some examples of international instruments that have provided for rights for people with disabilities include the World Programme of Action Concerning Disabled Persons, the Inter-American Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against People with Disabilities, and the Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities. There have also been international instruments dealing specifically with the rights of people with intellectual disabilities, such as the Montreal Declaration on Intellectual Disabilities. For a detailed history of the development of a rights-based approach to disability at the international level, see Marcia Rioux and Anne Carbert, ”Human Rights and Disability: The International Context” (2003) 10:2 Journal on Developmental Disabilities 1.

[8] Jonathan Kenneth Burns, “Mental Health and Inequity: A Human Rights Approach to Inequity, Discrimination and Mental Disability” (2009) 11:2 Critical Concepts 19 at 20.

[9] United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, Reporting Status for Canada, online: <http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/TreatyBodyExternal/Countries.aspx?CountryCode=CAN&Lang=EN>

[10] Armand de Mestral & Evan Fox-Decent, “Rethinking the Relationship Between International and Domestic Law” (2008) 53 McGill LJ 573 at para 48.

[11] Supra note 1 at 5.

[12] de Mestral & Fox-Decent supra note 10 at 617.

[13] Ibid at 583.

[14] In Baker v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), [1999] 2 SCR 817, 1999 CanLII 699 (SCC) [Baker] at 70, the Supreme Court discussed “the important role of international human rights law

as an aid in interpreting domestic law” and that it “is also a critical influence on the interpretation of the scope of the rights included in the Charter.” In Canada (Justice) v Khadr [2008] 2 SCR 125, 2008 SCC 28 at 17 the Supreme Court relied on R v Hape, [2007] 2 SCR 292, 2007 2 SCC 26 [Hape] to state that in interpreting the scope and application of the Charter, the courts should seek to ensure compliance with Canada’s binding obligations under international law. Justice Dickson of the Supreme Court of Canada in Slaight Communication Inc v Davidson, [1989] 1 SCR 1038, 1989 CanLII 92 (SCC) referred to his ruling in Reference Re Public Service Employee Relations Act (Alta), [1987] 1 SCR 313, 1987 CanLII 88 (SCC) where he stated, “the content of Canada’s international human rights obligations is, in my view, an important indicia of the meaning of the ‘full benefit of the Charter’s protection.’ I believe that the Charter should generally be presumed to provide protection at least as great as that afforded by similar provisions in international human rights documents which Canada has ratified.”

[15] Hape supra note 14 at 53.

[16] References and brief summaries of reported Canadian court and tribunal decisions are included as Appendix 1 to this paper.

[17] The actual number of reported court and tribunal decisions addressing the Convention is 22. However, two of those decisions, R v Myette, 2013 ABPC 89 and Nova Scotia (Community Services) v GP, 2016 NSFC 9, were cases that were reversed on appeal, including because the appellate court found that there had been errors in the way the Convention was addressed. In both cases the trial level courts treated the Convention positively and used the Convention to support broad and arguably novel reasoning in relation to the disability rights aspect of the cases. In both cases the appellate courts overturned this reasoning: see R v Myette, 2013 ABCA 371 and Nova Scotia (Community Services) v C.K.Z, 2016 NSCA 61 [Nova Scotia.] In order to understand the trends demonstrated by the case data, we have only counted each of these cases once when determining the total number of reported case and tribunal decisions addressing the Convention.

[18] According to data published by both the Canadian Human Rights Commission and the Ontario Human Rights Legal Support Centre, discrimination complaints on the grounds of disability are more common than discrimination complaints on all other grounds combined. Canadian Human Rights Commission, People First: The Canadian Human Rights Commission’s 2015 Annual Report to Parliament, (2015) at page 89; Human Rights Legal Support Centre, Annual Report 2015-2016, (2016) at page 3.

[19] 2011 HRTO 93.

[20] 2016 ONSC 7150.

[21] Supra note 14.

[22] Supra note 14.

[23] Cole v Cole, 2011 ONSC 4090 [Cole].

[24] Ibid at 6.

[25] Divorce Act, RSC 1985, c 3, s 2(1).s.

[26] Cole supra note 23 at 7.

[27] BS (Re) 2011, CanLII 26315 (ON CCB).

[28] Ibid at page 14.

[29] Nova Scotia supra note 17.

[30] Ibid at 42.

[31] See Appendix 2 for the full text of the Convention articles considered in this part of the paper.

Appendix 1: Summaries of Canadian Court and Tribunal Decisions Citing the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

Bailey v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration), 2014 FC 315

Judicial Review of a decision by a Senior Immigration Officer which refused the application for an exemption on humanitarian and compassionate grounds under s. 25(1) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act from the requirement to apply for a permanent resident visa from outside of Canada. The Applicant was a person with quadriplegia and sought an exemption based on the fact that there were inadequate medical care facilities to accommodate his disability. The Convention was not raised as an argument by the Applicant in this case, nor was it considered by the Court. In submitting that the Immigration Officer erred in her decision, the Applicant noted that the Officer quoted a US DOS Report but failed to take into account that the report itself noted that Jamaica (the Applicant’s home country) was a signatory to the Convention , but there were no reports that any action had been taken on behalf of Jamaica to implement the provisions of the Convention. The matter was returned to the Immigration Officer for reconsideration.

BS (Re) 2011, CanLII 26315 (ON CCB)

BS’ health practitioner brought an application before the Consent and Capacity Board for a determination as to whether or not the substitute decision-maker (BS’ spouse) had complied with section 21 of the Health Care Consent Act when she was making a decision with respect to proposed treatment for BS. BS was in a “vegetative state” and the proposed treatment was a palliative care plan that was opposed by BS’ substitute decision-maker. BS’ substitute-decision maker was represented by her son, AS, who was not a lawyer. AS raised the Article 25 of the Convention which states “that persons with disabilities have the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health without discrimination on the basis of disability.” The Board found that the Convention had no applicability in the matter and noted that “it is unclear what applicability the Convention has here absent “transformation” into Canadian law and no evidence was led related to discrimination.” [Emphasis added] The Board determined that the substitute decision-maker had not complied with the principles of substitute decision-making set out in the HCCA and directed her to consent to the proposed treatment plan.

Cole v. Cole (Litigation Guardian of), 2011 ONSC 4090

An Application and Cross-Application under the Substitute Decisions Act for the guardianship of the person and property of JP Cole by both his parents. The father argued that he still had custody of his son JP. The adult son with disabilities argued that his father did not have custody because once he became an adult he had legal capacity, was legally entitled to make his own decisions, and should be provided with supports to do so, in accordance with article 12 of the Convention. The judge disagreed with the son. The judge found that the father still had custody because Canada’s Divorce Act considers a person over the age of 18 to be a “child of the marriage” if they are unable because of their disability to live independently. The judge stated that he found the arguments about legal capacity and the Convention to be “interesting and worthy of consideration”, but nevertheless he could not derogate from the finding that the custody order still applied to the adult man on the basis of his disability because that is what is provided for in Canadian law.

Cole v. Ontario (Health and Long-term Care), 2015 HRTO 521

The issue before the Tribunal was whether a cap on nursing services pursuant to Ontario Regulation 386/99 made under the Home Care and Community Services Act, 1994 contravenes the Human Rights Code. As a result of the cap, the Applicant did not have funding for a fifth catheterization that he required. In this interim decision, the Bazelon Centre for Mental Health Law (“Bazelon Centre”) sought leave to intervene in the matter, to provide information and comparative perspective about how the US anti-discrimination laws have defined the right to community. Bazelon Centre submitted that this information would provide a valuable perspective in interpreting the Code and the Convention. The Human Rights Tribunal denied Bazelon Centre intervener status. The Tribunal found that any assistance proposed by Bazelon Centre, including providing relevant US jurisprudence, could be provided by the parties.

Cruden v. Canadian International Development Agency and Health Canada, 2011 CHRT 13

Complainant alleged CIDA discriminated by concluding she was unsuitable for a posting in Afghanistan for failure to meet medical requirements due to type 1 diabetes. Complainant previously had to be flown home from Afghanistan due to diabetes. Complainant’s personal doctor and a Health Canada doctor had medically cleared her to return, however Health Canada’s Afghanistan Guidelines categorized her as unfit. The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal found that CIDA would have experienced undue hardship in accommodating the claimant in Afghanistan. However, the Tribunal stated that CIDA had a procedural duty to explore appropriate accommodations and there was insufficient evidence showing that CIDA seriously considered accommodations. The Tribunal cited Articles 10 and 11 of the Convention. The Tribunal ordered various systemic remedies be implemented by Health Canada and CIDA, and that the claimant be posted to a country with appropriate medical facilities.

Note: This decision was reversed at the Federal Court, and reversal was affirmed at the Federal Court of Appeal, with no mention of the Convention in either decision.

DP1 Inc v. Holland, 2016 YKSC 44

Application for the adjournment of a civil case until an accommodation plan was put in place for the moving party by the Court. The adjournment was granted in part. The plaintiff raised the Convention but the Court did not deal with the Convention in its decision.

Grant v. Manitoba Telecom Services Inc., 2012 CHRT 10

The applicant alleged discrimination based on disability – she had received medical leave and a transfer due to newly diagnosed type II diabetes and difficulty controlling her blood sugar. Her performance reviews then became worse and she was terminated in a restructuring. The Tribunal cites the preamble to the Convention, after outlining the purpose of the CHRA. The Tribunal noted that the quoted section of the Convention is “in the same vein” as the purpose of the CHRA. The Tribunal found that the respondent did discriminate against the applicant by not considering her disability properly when evaluating her performance. Various specific and public interest remedies are ordered.

Geldart v. Geldart, 2016 ONSC 7150 (CanLII)

Motion by SG to set aside a default judgment for failing to attend an appointed trial date in a civil proceeding about the right to share in profits from the sale of a family home. SG’s lawyer terminated the retainer shortly before trial, and SG could not secure another lawyer. SG had Generalized Anxiety Disorder and believed she could not represent herself at trial.

The Court cited Article 13(1) of the Convention and stated that 52.01(2) and (3) of the Rules of Civil Procedure must be interpreted in a manner consistent with Canada’s international Human Rights obligations, which require equal access to justice. The Court stated that, “preserving [SG’s] access to justice requires the court to apply Rule 52.01(2) as a mechanism that permits a person with a recognized disability to proceed to a trial of the action on the merits, with legal representation, where her initial failure to attend is reasonably attributable to her heightened emotional response to her lawyer’s removal from the case on the eve of trial, and the pronouncements of the pre-trial conference judge, amplified by her psychological disorder.” Default judgment set aside.

Hinze v. Great Blue Heron Casino, 2011 HRTO 93

Application alleging discrimination on the grounds of disability. The Convention was not raised by the applicant. In determining that the applicant was not disabled within the meaning of Ontario`s Human Rights Code, the Tribunal member explained that the Tribunal would be using a social model definition of disability. The Tribunal relied upon the Convention and various Supreme Court decisions.

Kacan v. Ontario Public Service Employees Union, 2010 HRTO 795

Interim decision of a human rights application alleging discrimination by members of a union who were picketing outside the group homes of persons labelled with disabilities. The respondent raised capacity concerns about the claimant and asked the Tribunal to inquire into whether the claimant needed a litigation guardian. The Tribunal found that the Human Rights Code and common law promote autonomy and dignity for persons with disabilities. The Tribunal relied on Article 12 of the Convention to further support this reasoning.

National Capital Commission v. Brown, 2008 FC 733

An application for Judicial Review from a Canadian Human Rights Tribunal decision which found that the NCC discriminated against Brown in the provision of services on the ground of disability by failing to provide universal access at the York Street Steps in Ottawa. The intervener, Council of Canadians with Disabilities, submitted that the duty to accommodate includes the duty to consult with people with disabilities. The intervener relied on Canada’s national policies in the field and its international obligations as signatory to the Convention.

The Federal Court quashed the CHRT decision finding that the Tribunal erred in finding a legal duty to consult within the Canadian Human Rights Act. The Court did not address the Convention directly, but did reject the argument that relied on the Convention.

Note: the Federal Court of Appeal overturned this decision and sent the matter back to the CHRT for a new determination.

Note: this case was decided when Canada had signed but not ratified the Convention

Nova Scotia (Community Services) v. C.K.Z, 2016 NSCA 61

The Court of Appeal overturned a Family Court decision that relied, in part, upon the Convention to dismiss an application by the Minister for permanent care of two children born to a couple with intellectual disabilities. The Family Court analyzed the best interests of the children, and as part of this analysis considered whether appropriate disability services and supports had been provided to the parents. The Family Court relied upon Article 23 of the Convention, which provides for respect for the home and family. The Court of Appeal ruled that the trial judge did not focus appropriately on the best interests of the children and erroneously focused on the parents. The Court of Appeal found that the trial judge did not follow domestic legal precedent and instead erroneously relied on the Convention to support a new kind of best interests of the child analysis. The Court of Appeal also commented that it is unclear how two ratified international treaties, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, should interact in this instance absent domestic incorporation

Note: This decision was appealed to the Supreme Court on November 2, 2016.

Portman v. Northwest Territories, 2014 CanLII 21552 (NT HRAP)

Portman filed an application to have publicly-funded legal counsel appointed to represent her in two human rights complaints, both having to do with a disability insurance policy that she alleged was discriminatory on the grounds of disability. The Appellant referred to the preamble of the Human Rights Act (HRA) and submitted that it brought in Article 13 of the CRPD which obliges state parties to “ensure effective access to justice with persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others” and submitted that this required the Respondents to provide her with counsel to represent her in her complaints. The Panel found that, while the Convention may be an international human rights instrument of vital importance, as referred to by the HRA, the preamble did not incorporate the requirements of the Convention into the HRA. The Panel further determined that the Convention only requires states to ensure that persons with disabilities have access to justice on an equal basis with others and that this was not a requirement to ensure persons with disabilities had publicly-funded counsel. The Panel dismissed the application without a hearing.

Portman v. Northwest Territories (Department of Justice), 2016 CanLII 47992 (NT HRAP)

Appeal to the Tribunal from the Director’s dismissal of Portman’s application in 2014 (see above, Portman (2014). The Human Rights Adjudication Panel found that Portman’s previous complaint was dismissed unfairly and she was entitled to a hearing. At said hearing, it was found that Legal Aid both systemically discriminates against persons with disabilities and specifically discriminated against Portman. The Convention was used as an interpretive aid to the Northwest Territories Human Rights legislation.

R. v. Ejigu, 2016 BCSC 1487

Second degree murder case. The accused challenged the balance of probabilities standard for Not Criminally Responsible on Account of Mental Disorder, pursuant to R v Chaulk, on the grounds that government documents like the Convention and others indicate society’s shifting attitudes towards substantive equality and the stigmatization and segregation of persons with mental health disabilities. Sections 16(2) and s.16(3) of the Criminal Code were found to violate the Charter section 7, 15(1), and 11(d), but are were saved by section 1. The Court did not engage with the content of the Convention, but did state that the treaty was insufficient evidence of the “fundamental shift in the parameters of the debate” required for a trial judge to revisit established Charter jurisprudence.

R. v. Myette, 2013 ABPC 89

Sentencing hearing. The accused was convicted of sexual assault and was blind, requiring 24 hour assistance from a guide dog. The Crown asked for 18 months to 2 years incarceration. The defense argued that the correctional facility did not accommodate the accused’s disability-based needs, and that the sentence of incarceration proposed by the Crown was in breach of Article 14 of the Convention. Defence further argued that if the accused was to be deprived of his liberty then he was entitled to guarantees in accordance with the Convention and while he was incarcerated he must be provided with reasonable accommodation. The Court found that the evidence showed there was nothing approaching reasonable accommodation in prisons. The court found that placing the accused in jail would contravene both s.718 of the Criminal Code and the Convention by being unduly harsh and depriving the accused of liberty in a way that would be disproportionate to non-disabled prisoners. A suspended sentence of 18 months was given, with home arrest.

R. v. Myette, 2013 ABCA 371

The Crown appealed from the above decision. The majority of the Court

determined that the sentence was demonstrably unfit and found that the

sentencing judge “overemphasized the circumstances of the offender” and failed

to consider the proportionate gravity of the offence; house arrest was a

conditional sentence no longer available for this kind of offence. The majority

disagreed with most of the sentencing judge’s findings and reached a different

conclusion from the evidence put before the Court by both parties with respect

to accommodations available in correctional facilities. The Court found that

the judge’s conclusion that reasonable accommodation in the correctional

facility was not attainable and therefore the Convention was breached was flawed.

The Court further rejected the Trial Judge`s conclusion that an alleged

breach of the Convention was a

presumptive breach of domestic law for sentencing purposes. The majority

allowed the appeal and substituted a sentence of imprisonment of 90 days to be

served on an intermittent basis.

Saporsantos Leobrera v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship & Immigration), 2010 FC 587

An application for judicial review pursuant to subsection 72(1) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act from a decision of an immigration officer denying the Applicant’s humanitarian and compassionate grounds application. The Applicant was a 23 year-old person with an intellectual disability, living in the Philippines. The Federal Court engaged in an in-depth discussion with respect to the definition of a “child.” The Applicant’s mother, who is a Canadian citizen but was barred from sponsoring her daughter, submitted that in light of her disability the 23 year-old applicant should be considered a “child” for the purposes of the “best interests of the child” analysis. The court found this reasoning problematic and referred to Canada’s ratification of the Convention. The Court found that the language used in the Convention did not support the argument that adults with disabilities can be deemed to be “children” for this purpose, since the Convention draws a distinction between children with disabilities and adults with disabilities. The court concluded that it is evident that the Convention supports the argument that childhood is a temporary state which is determined by age and not by personal characteristics. The Immigration Officer’s decision was quashed on the basis that the Officer erroneously removed documents from the application and the matter was sent back to a new Officer for determination.

Sunshine Transit Services v. Taxicab Board, 2014 MBCA 33

Application for leave to appeal to the Manitoba Court of Appeal pursuant to s19.2 (1) of The Taxicab Act from a decision of the Taxicab Board. The Applicant had applied to the Board for a Specialty Vehicle Business License to operate a wheelchair accessible limousine vehicle service – there were no such limousine services in Winnipeg. At the hearing before the Board the owner of the Applicant business argued that the Board needed to provide equal accessibility for persons with disabilities to limousine services in Winnipeg. He requested that the Board take into consideration the international human rights standards of persons with disabilities as set out in the Convention. He submitted that making this limousine service available would improve “making Winnipeg truly accessible and provide transportation to all segments of society.” The Board denied the application, and the Court denied leave to appeal, finding that the Board considered the needs and interests of persons with disabilities but the Applicant did not present a compelling case that there was sufficient demand to justify a license. The Court did not address the Convention.

Tanudjaja v. Attorney General (Canada), 2013 ONSC 1878 (CanLII)

Interim decision regarding multiple motions to intervene in a motion to dismiss an application by the Centre for Equality Rights in Accommodation alleging that adequate housing is a human right protected by sections 7 and 15 of the Charter. The Court permitted Amnesty International to make submissions restricted to demonstrating how specific international treaties (including the Convention) may assist in determining how s. 7 and s. 15 of the Charter could be interpreted such that it is not plain and obvious that the application cannot succeed.

Note: In the subsequent decision on the merits, Lederer, J. did not find any international law relevant to the issues before the court. The application was dismissed on the basis that the claim was not justiciable. Lederer, J.`s decision was upheld by the Ontario Court of Appeal.

Yuill v. Canadian Union of Public Employees, 2011 HRTO 126

Interim decision regarding whether the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario

had jurisdiction to appoint a litigation guardian. The Tribunal found that it

did have jurisdiction to appoint a litigation guardian for a claimant when the

proposed guardian was willing to take on the role. The Tribunal relied on

Article 13 of the Convention in

conjunction with the Code and the SPPA to find that the relevant

legislation should be interpreted in a manner that facilitates access to the

Tribunal for persons with disabilities while also providing appropriate

safeguards.

Appendix 2: Text of Select Convention Articles Referred to in this Paper

Article 3 – General principles

The principles of the present Convention shall be:

- Respect for inherent dignity, individual autonomy including the freedom to make one’s own choices, and independence of persons;

- Non-discrimination;

- Full and effective participation and inclusion in society;

- Respect for difference and acceptance of persons with disabilities as part of human diversity and humanity;

- Equality of opportunity;

- Accessibility;

- Equality between men and women;

- Respect for the evolving capacities of children with disabilities and respect for the right of children with disabilities to preserve their identities.

Article 4 – General obligations

- States Parties undertake to ensure and promote the full realization of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all persons with disabilities without discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability. To this end, States Parties undertake:

- To adopt all appropriate legislative, administrative and other measures for the implementation of the rights recognized in the present Convention;

- To take all appropriate measures, including legislation, to modify or abolish existing laws, regulations, customs and practices that constitute discrimination against persons with disabilities;

- To take into account the protection and promotion of the human rights of persons with disabilities in all policies and programmes;

- To refrain from engaging in any act or practice that is inconsistent with the present Convention and to ensure that public authorities and institutions act in conformity with the present Convention;

- To take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination on the basis of disability by any person, organization or private enterprise;

- To undertake or promote research and development of universally designed goods, services, equipment and facilities, as defined in article 2 of the present Convention, which should require the minimum possible adaptation and the least cost to meet the specific needs of a person with disabilities, to promote their availability and use, and to promote universal design in the development of standards and guidelines;

- To undertake or promote research and development of, and to promote the availability and use of new technologies, including information and communications technologies, mobility aids, devices and assistive technologies, suitable for persons with disabilities, giving priority to technologies at an affordable cost;

- To provide accessible information to persons with disabilities about mobility aids, devices and assistive technologies, including new technologies, as well as other forms of assistance, support services and facilities;

- To promote the training of professionals and staff working with persons with disabilities in the rights recognized in this Convention so as to better provide the assistance and services guaranteed by those rights.

- With regard to economic, social and cultural rights, each State Party undertakes to take measures to the maximum of its available resources and, where needed, within the framework of international cooperation, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of these rights, without prejudice to those obligations contained in the present Convention that are immediately applicable according to international law.

- In the development and implementation of legislation and policies to implement the present Convention, and in other decision-making processes concerning issues relating to persons with disabilities, States Parties shall closely consult with and actively involve persons with disabilities, including children with disabilities, through their representative organizations.

- Nothing in the present Convention shall affect any provisions which are more conducive to the realization of the rights of persons with disabilities and which may be contained in the law of a State Party or international law in force for that State. There shall be no restriction upon or derogation from any of the human rights and fundamental freedoms recognized or existing in any State Party to the present Convention pursuant to law, conventions, regulation or custom on the pretext that the present Convention does not recognize such rights or freedoms or that it recognizes them to a lesser extent.

- The provisions of the present Convention shall extend to all parts of federal states without any limitations or exceptions.

Article 6 – Women with disabilities

- States Parties recognize that women and girls with disabilities are subject to multiple discrimination, and in this regard shall take measures to ensure the full and equal enjoyment by them of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.

- States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to ensure the full development, advancement and empowerment of women, for the purpose of guaranteeing them the exercise and enjoyment of the human rights and fundamental freedoms set out in the present Convention.

Article 9 – Accessibility

- To enable persons with disabilities to live independently and participate fully in all aspects of life, States Parties shall take appropriate measures to ensure to persons with disabilities access, on an equal basis with others, to the physical environment, to transportation, to information and communications, including information and communications technologies and systems, and to other facilities and services open or provided to the public, both in urban and in rural areas. These measures, which shall include the identification and elimination of obstacles and barriers to accessibility, shall apply to, inter alia:

- Buildings, roads, transportation and other indoor and outdoor facilities, including schools, housing, medical facilities and workplaces;

- Information, communications and other services, including electronic services and emergency services.

- States Parties shall also take appropriate measures to:

- Develop, promulgate and monitor the implementation of minimum standards and guidelines for the accessibility of facilities and services open or provided to the public;

- Ensure that private entities that offer facilities and services which are open or provided to the public take into account all aspects of accessibility for persons with disabilities;

- Provide training for stakeholders on accessibility issues facing persons with disabilities;

- Provide in buildings and other facilities open to the public signage in Braille and in easy to read and understand forms;

- Provide forms of live assistance and intermediaries, including guides, readers and professional sign language interpreters, to facilitate accessibility to buildings and other facilities open to the public;

- Promote other appropriate forms of assistance and support to persons with disabilities to ensure their access to information;

- Promote access for persons with disabilities to new information and communications technologies and systems, including the Internet;

- Promote the design, development, production and distribution of accessible information and communications technologies and systems at an early stage, so that these technologies and systems become accessible at minimum cost.

Article 13 – Access to justice

- States Parties shall ensure effective access to justice for persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others, including through the provision of procedural and age-appropriate accommodations, in order to facilitate their effective role as direct and indirect participants, including as witnesses, in all legal proceedings, including at investigative and other preliminary stages.

- In order to help to ensure effective access to justice for persons with disabilities, States Parties shall promote appropriate training for those working in the field of administration of justice, including police and prison staff.

Article 20 – Personal mobility

States Parties shall take effective measures to ensure personal mobility with the greatest possible independence for persons with disabilities, including by:

- Facilitating the personal mobility of persons with disabilities in the manner and at the time of their choice, and at affordable cost;

- Facilitating access by persons with disabilities to quality mobility aids, devices, assistive technologies and forms of live assistance and intermediaries, including by making them available at affordable cost;

- Providing training in mobility skills to persons with disabilities and to specialist staff working with persons with disabilities;

- Encouraging entities that produce mobility aids, devices and assistive technologies to take into account all aspects of mobility for persons with disabilities.

Article 21 – Freedom of expression and opinion, and access to information

States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to ensure that persons with disabilities can exercise the right to freedom of expression and opinion, including the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas on an equal basis with others and through all forms of communication of their choice, as defined in article 2 of the present Convention, including by:

- Providing information intended for the general public to persons with disabilities in accessible formats and technologies appropriate to different kinds of disabilities in a timely manner and without additional cost;

- Accepting and facilitating the use of sign languages, Braille, augmentative and alternative communication, and all other accessible means, modes and formats of communication of their choice by persons with disabilities in official interactions;

- Urging private entities that provide services to the general public, including through the Internet, to provide information and services in accessible and usable formats for persons with disabilities;

- Encouraging the mass media, including providers of information through the Internet, to make their services accessible to persons with disabilities;

- Recognizing and promoting the use of sign languages.

Article 27 – Work and employment

- States Parties recognize the right of persons with disabilities to work, on an equal basis with others; this includes the right to the opportunity to gain a living by work freely chosen or accepted in a labour market and work environment that is open, inclusive and accessible to persons with disabilities. States Parties shall safeguard and promote the realization of the right to work, including for those who acquire a disability during the course of employment, by taking appropriate steps, including through legislation, to, inter alia:

- Prohibit discrimination on the basis of disability with regard to all matters concerning all forms of employment, including conditions of recruitment, hiring and employment, continuance of employment, career advancement and safe and healthy working conditions;

- Protect the rights of persons with disabilities, on an equal basis with others, to just and favourable conditions of work, including equal opportunities and equal remuneration for work of equal value, safe and healthy working conditions, including protection from harassment, and the redress of grievances;

- Ensure that persons with disabilities are able to exercise their labour and trade union rights on an equal basis with others;

- Enable persons with disabilities to have effective access to general technical and vocational guidance programmes, placement services and vocational and continuing training;

- Promote employment opportunities and career advancement for persons with disabilities in the labour market, as well as assistance in finding, obtaining, maintaining and returning to employment;

- Promote opportunities for self-employment, entrepreneurship, the development of cooperatives and starting one’s own business;

- Employ persons with disabilities in the public sector;

- Promote the employment of persons with disabilities in the private sector through appropriate policies and measures, which may include affirmative action programmes, incentives and other measures;

- Ensure that reasonable accommodation is provided to persons with disabilities in the workplace;

- Promote the acquisition by persons with disabilities of work experience in the open labour market;

- Promote vocational and professional rehabilitation, job retention and return-to-work programmes for persons with disabilities.

- States Parties shall ensure that persons with disabilities are not held in slavery or in servitude, and are protected, on an equal basis with others, from forced or compulsory labour.

Article 28 – Adequate standard of living and social protection

- States Parties recognize the right of persons with disabilities to an adequate standard of living for themselves and their families, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions, and shall take appropriate steps to safeguard and promote the realization of this right without discrimination on the basis of disability.

- States Parties recognize the right of persons with disabilities to social protection and to the enjoyment of that right without discrimination on the basis of disability, and shall take appropriate steps to safeguard and promote the realization of this right, including measures:

- To ensure equal access by persons with disabilities to clean water services, and to ensure access to appropriate and affordable services, devices and other assistance for disability-related needs;

- To ensure access by persons with disabilities, in particular women and girls with disabilities and older persons with disabilities, to social protection programmes and poverty reduction programmes;

- To ensure access by persons with disabilities and their families living in situations of poverty to assistance from the State with disability-related expenses, including adequate training, counselling, financial assistance and respite care;

- To ensure access by persons with disabilities to public housing programmes;

- To ensure equal access by persons with disabilities to retirement benefits and programmes.

Article 29 – Participation in political and public life

States Parties shall guarantee to persons with disabilities political rights and the opportunity to enjoy them on an equal basis with others, and shall undertake to:

- Ensure that persons with disabilities can effectively and fully participate in political and public life on an equal basis with others, directly or through freely chosen representatives, including the right and opportunity for persons with disabilities to vote and be elected, inter alia, by:

- Ensuring that voting procedures, facilities and materials are appropriate, accessible and easy to understand and use;

- Protecting the right of persons with disabilities to vote by secret ballot in elections and public referendums without intimidation, and to stand for elections, to effectively hold office and perform all public functions at all levels of government, facilitating the use of assistive and new technologies where appropriate;

- Guaranteeing the free expression of the will of persons with disabilities as electors and to this end, where necessary, at their request, allowing assistance in voting by a person of their own choice;

- Promote actively an environment in which persons with disabilities can effectively and fully participate in the conduct of public affairs, without discrimination and on an equal basis with others, and encourage their participation in public affairs, including:

- Participation in non-governmental organizations and associations concerned with the public and political life of the country, and in the activities and administration of political parties;

- (ii) Forming and joining organizations of persons with disabilities to represent persons with disabilities at international, national, regional and local levels.

Article 30 – Participation in cultural life, recreation, leisure and sport

- States Parties recognize the right of persons with disabilities to take part on an equal basis with others in cultural life, and shall take all appropriate measures to ensure that persons with disabilities:

- Enjoy access to cultural materials in accessible formats;

- Enjoy access to television programmes, films, theatre and other cultural activities, in accessible formats;

- Enjoy access to places for cultural performances or services, such as theatres, museums, cinemas, libraries and tourism services, and, as far as possible, enjoy access to monuments and sites of national cultural importance.

- States Parties shall take appropriate measures to enable persons with disabilities to have the opportunity to develop and utilize their creative, artistic and intellectual potential, not only for their own benefit, but also for the enrichment of society.

- States Parties shall take all appropriate steps, in accordance with international law, to ensure that laws protecting intellectual property rights do not constitute an unreasonable or discriminatory barrier to access by persons with disabilities to cultural materials.

- Persons with disabilities shall be entitled, on an equal basis with others, to recognition and support of their specific cultural and linguistic identity, including sign languages and deaf culture.

- With a view to enabling persons with disabilities to participate on an equal basis with others in recreational, leisure and sporting activities, States Parties shall take appropriate measures:

- To encourage and promote the participation, to the fullest extent possible, of persons with disabilities in mainstream sporting activities at all levels;

- To ensure that persons with disabilities have an opportunity to organize, develop and participate in disability-specific sporting and recreational activities and, to this end, encourage the provision, on an equal basis with others, of appropriate instruction, training and resources;

- To ensure that persons with disabilities have access to sporting, recreational and tourism venues;

- To ensure that children with disabilities have equal access with other children to participation in play, recreation and leisure and sporting activities, including those activities in the school system;

- To ensure that persons with disabilities have access to services from those involved in the organization of recreational, tourism, leisure and sporting activities.

Article 31 – Statistics and data collection

- States Parties undertake to collect appropriate information, including statistical and research data, to enable them to formulate and implement policies to give effect to the present Convention. The process of collecting and maintaining this information shall:

- Comply with legally established safeguards, including legislation on data protection, to ensure confidentiality and respect for the privacy of persons with disabilities;

- Comply with internationally accepted norms to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms and ethical principles in the collection and use of statistics.

- The information collected in accordance with this article shall be disaggregated, as appropriate, and used to help assess the implementation of States Parties’ obligations under the present Convention and to identify and address the barriers faced by persons with disabilities in exercising their rights.

- States Parties shall assume responsibility for the dissemination of these statistics and ensure their accessibility to persons with disabilities and others.

Article 32 – International cooperation

- States Parties recognize the importance of international cooperation and its promotion, in support of national efforts for the realization of the purpose and objectives of the present Convention, and will undertake appropriate and effective measures in this regard, between and among States and, as appropriate, in partnership with relevant international and regional organizations and civil society, in particular organizations of persons with disabilities. Such measures could include, inter alia:

- Ensuring that international cooperation, including international development programmes, is inclusive of and accessible to persons with disabilities;

- Facilitating and supporting capacity-building, including through the exchange and sharing of information, experiences, training programmes and best practices;

- Facilitating cooperation in research and access to scientific and technical knowledge;

- Providing, as appropriate, technical and economic assistance, including by facilitating access to and sharing of accessible and assistive technologies, and through the transfer of technologies.

- The provisions of this article are without prejudice to the obligations of each State Party to fulfil its obligations under the present Convention.